|

In this issue EDITORIAL: Web Presence WEB PRESENCE: What is your Web presence? WEB PRESENCE: Getting the perfect domain name WEB PRESENCE: Choosing an email provider: Your biggest decision WEB PRESENCE: Choosing a web-hosting service: The ins and outs WEB PRESENCE: Building your business website: Understanding the options WEB PRESENCE: Working with search engines WEB PRESENCE: Business social networking WEB PRESENCE: Currency, continuity, and commitment

EDITORIAL SPECIAL EDITION: Web Presence

By Will Fastie Freedom! For our US-based readership, today is a celebration of freedom and liberty. To add our little bit to the festivities, we are “liberating” eight articles previously available only to Plus members. And for Plus members, you’ll now have this entire set in one, ad-free place. I’m talking about the “Web Presence” series I wrote for Woody in the second half of 2020. In the series, I tried to provide a comprehensive primer about living on the Web and especially about creating and maintaining your own website, whether for personal or business reasons. The series touches on domains, email, social networks, development, and more. The eight articles are presented as they were originally, although I have made a few very, very minor updates to reflect conditions today. Most of those changes involve cost estimates, to which I should add that I’m expecting all prices to rise going forward. Budget wisely. The series often mentions business, which was part of my charge at the time. However, almost everything in the series applies equally to personal or hobby sites. The articles are presented in chronological order. I also updated the formatting of each article to match the way we publish articles today. Importantly, the forum link for each article (in the orange “Talk Bubbles” box at the end) points to the original forum topic, so you’ll be able to see what folks had to say at the time. We look forward to your more current observations and comments. Thanks for reading, and thanks for being a part of our growing community.

Will Fastie is editor in chief of the AskWoody Plus Newsletter. WEB PRESENCE What is your Web presence?

By Will Fastie Nearly everyone who spends time on the Internet has some sort of Web presence. What do we mean by “presence?” Google your name or the name of your business. What’s the result? Nothing? Hundreds of references? That’s one crude measurement of Web presence or exposure, but there are many other forms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, YouTube, podcasts, published works, forum postings, a personal or business website, and lots more. For businesses and professionals, the quality of Web exposure is far more important than the magnitude. To the extent possible, you want to be in control of how and where potential customers find you on the Internet. The simplest and least expensive way to establish your Web persona is through social networking. Setting up a Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter account is exceptionally easy — both for personal and business purposes. YouTube is another free and powerful platform for establishing a Web presence, although creating effective videos is often time-consuming and potentially expensive. We might be drawn to social networking like bears to honey, but there are hidden costs to these platforms: primarily a loss of privacy and control. You could be throwing yourself into unfriendly waters, and you certainly don’t want to become lost in the chaos of “stuff” floating around social networks. In recent years there’s also been growing debate over censorship, with the network providers deciding what content constitutes a terms-of-service violation. In short: Relying on social networking for enhancing your prominence on the Internet could be a difficult balancing act. Here’s an example of the social-networking uncertainty factor. According to an article in The Verge, YouTube’s ad service may block revenue generated by channels that make even passing references to COVID-19 and the pandemic. One publisher even tried “code” words to circumvent the demonetizing policy. But for the typical business, that’s a needless distraction. The solution for most businesses and professionals is to establish a dedicated website as the foundation of your Web presence — and use other services as adjuncts. As long as the content you create isn’t slanderous, libelous, or defamatory, you can put whatever you like on your site. You have total control. What’s required for a dedicated website

MONEY! Nearly all personal and business websites are “hosted” on third-party services such as bluehost, GoDaddy, HostGator, Squarespace, and many others. The fees these services charge are relatively modest, but they will still make some small businesses wince. (I’ve found many small firms to be extraordinarily sensitive to any recurring charge, no matter how small.) And, yes, there are offers out there for free domains. Read the fine print carefully — nothing is truly free. A custom website must become just another cost of doing business — and those costs are rising. In the early days of the Web, hosting services offered aggressive and attractive discounts based on volume or with long-term contracts. But that’s rarely the case today. In the following sections, I’ll give very rough cost estimates for the various website services. Use them as a general guide for budgeting and planning. And be prepared for rising site expenses. (Note: I’ve tended to err on the high side.) Tip: An all-in-one website service might be tempting, but using multiple vendors is the better bet. It’ll make administration a bit more time-consuming, but it gives you far more control. Moreover, ongoing site changes will be easier. And ultimately, you’ll probably have a much stronger Web presence. DOMAIN NAME: The central tenet to Web presence is identity — not just for your site, but for the business or profession as a whole. So when creating a website, the most important (and sometimes difficult) decision is often settling on a site’s domain name — its online signature. The domain name is critically important for several reasons. It’s not just how you’ll be known on the Internet, it’ll almost always be used for email — and it might also be the title for Facebook pages, YouTube channels, Twitter tags, and so forth. This is like naming your kid! Take some time to consider the benefits and consequences, because it’ll be with you for a long time. There’s another complication to choosing a domain name: availability. If your business name is, say, AAA Plumbing, good luck finding a similar domain name. (You almost might be better off changing the name of the company.) Fortunately, the domain-name space has been expanding. Early on, I was lucky to get my personal domain name. But when I created my business site, a .com version wasn’t available. However, I was able to snag one with a .biz extension. At one time, “top-level” domain extensions were limited to the well-known .org, .com, .gov, and a few others. Now there are hundreds of domain extensions (more info). So for businesses, a .com extension is no longer essential — just desirable. The price for a domain name is a bit like a commodities market: simple supply and demand. The so-called “domain name registrars,” the companies that rent us domain names, will often jack up the initial fee for popular monikers — sometimes to astronomical levels. I let a domain name of a deceased friend lapse, and today the asking price is USD $3,000 for the first year. After the initial buy, prices might fall to a more reasonable level, though not always. I recommend budgeting around $25 per year for the domain name Note: Do not — I repeat, do not — purchase a multi-year domain-name contract. There’s almost never a discount, and a one-year term will ensure you get an annual reminder about your ownership. Some of my clients with longer contracts forgot to make timely payments and lost ownership of their domain — a Web-presence cardinal sin. (There’s a legend that a major tech publication once forgot to pay its domain-name fee and was on the cusp of losing it. But an astute copy editor noticed and paid the bill with a personal credit card.) Also, shorter terms can save you money when changing domain registrars (more info). EMAIL: Logically, the next step is to investigate Web-hosting plans. But first, you must consider email solutions and choose the best fit for your business. An email address is critical to your Web presence because it’s often the primary link between your website, your business, and your customers. (It’s simply more professional to have an email address that matches your site’s domain name.) Note that almost all Web-hosting plans include email service. But I don’t recommend using it, for two important reasons. First, email services offered by hosting sites often have a limited capacity. No matter what the Web host says, there is no such thing as “unlimited” email storage. One way or another, there are hard limits — and, depending on the nature of the business, email can quickly consume lots of storage. Business managers don’t want to worry about a full inbox space or the email system soaking up the entire storage capacity of the hosting plan. Second, using the Web host’s email plan tends to lock you into that host. You can usually move your website to another host at will, but moving years’ worth of emails could present significant challenges. It might require a consulting expert. I recommend setting up an account with an independent email service such as Microsoft 365, Google’s G Suite, or ProtonMail. There are many others to choose from. Separate email services will often give you better features, better performance, better spam-checking, better everything. Budget at least $5 per “user” account per month. Assume that you’ll have at least one and possibly two accounts, such as info@… or admin@… . Consider how many people in your business will need an account. Email could make up a significant part of your Web-presence budget. But a separate service will be worth the cost — especially if you need to move to another website-hosting company. WEBSITE HOSTING: Simply put, websites are just applications that need a continuous and permanent connection to the World Wide Web. Hosting services provide both the hardware to run your site and a reliable, high-speed link to the Web. (A slow site is another Web-presence sin.) There are hundreds of hosts to choose from, and, not surprisingly, a bewildering range of prices and features. Here’s what to look for.

And again, I recommend one-year (or even monthly) contracts so you can move to another host without incurring a significant financial penalty. Budget $20 per month and pay annually. You’ll probably pay less initially, but you want a cushion in case you add additional features or domains. I maintain four websites and pay just $13 per month for hosting — including SSL certificates! (That doesn’t include the “rental” of the domain names.) There are numerous under-$20 options around, but keep in mind that prices are expected to rise. MOST IMPORTANT: Small-business owners must ensure that they own their Web assets directly, and not through third parties such as the developer who built the site. In other words, accounts for domain-name registration, hosting, email service, and social media need to be in the business’s or business owner’s name — regardless of the trust you’ve placed in those who help build and maintain the site. Also, be sure you retain ownership of the design, code, and data. Your site is a critical business asset that you need to protect and secure.

Will Fastie is a Web developer specializing in self-service websites for small businesses. Trained in computer science at Johns Hopkins University, he has held positions as a transaction processing systems programmer, magazine editor, newsletter publisher, Wall Street analyst, CTO, and systems consultant. Shortly after writing this Web Presence series for Woody, he became the editor in chief of this newsletter.

WEB PRESENCE Getting the perfect domain name: The brand

By Will Fastie Visit a registrar, buy a domain name, and you’re done, right? Not quite. Those are the last steps. Before getting to that point, it’s important to understand what you are buying, whom you should buy it from, why domain-name registrars are important, what you need from a registrar, and — most important — what your brand will be. Your domain name will be with you for (hopefully) a long time, and giving the decision the time and thought it deserves can pay dividends into the future. On the other hand, if you have a brainstorm and see the perfect domain name in your mind’s eye, don’t fool around — buy it, and deal with the details later. The truth is that domain names are cheap (relatively speaking), and if you need to make a change later, you can do so. Domain names are assets

I cannot emphasize this point too much. If you are the proprietor of, say, Joe’s Hardware Store, you probably have a sign over the door that says “Joe’s Hardware Store.” That sign is an asset. You paid good money for it, it identifies your location, and it’s even a form of advertising. But because it is physical, it is easier to think of it as an asset rather than something virtual and somewhat ethereal, such as a domain name. But domain names are no less an asset than the sign over a retail store’s door, and it is extremely important that they be treated and protected the same as any other business asset. As a Web developer, I have too many stories about clients who did not take this point seriously. What drives the point home is the loss of the asset. Those who do not consider a domain name an important business asset risk losing it through carelessness. Once lost, a domain name is expensive or even impossible to recover. The loss of a domain name can be a setback to your Web presence. It is also important to understand that domain names can only be leased, not purchased, so protecting your “ownership” of a domain name means keeping up on the lease payments, religiously. Understanding domain names

A domain name consists of a name, such as joes-hardware, and what is known as a “top-level domain,” or TLD, such as com. A website can also have “sub-domains,” whose names are prefixed to a domain name. The pieces of this part of a URL are connected via punctuation, in this case dots (periods). Thus store.joes-hardware.com might refer to an online ordering system for Joe’s Hardware Store. Notice that the top-level domain is last. The domain portion of a URL reads backwards, right to left between the punctuation marks. The part you must lease is the name followed by a TLD, and that portion is called the domain name. Sub-domains do not need to be leased. They can be chosen by you, to the extent that your Web-hosting plan allows. Thus, choosing a domain name consists of finding a name/TLD combination that suits you and is not already taken. For example, if you want fastie.com, you’re out of luck — that one belongs to me. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a gold rush for the TLD com. There were two reasons for that. First, there were at the time very few TLDs available, and most of the non-coms were limited to specific segments such as government, military, non-profit, and education. Despite its designation for commerce, com was chosen for everything else. Second, com became associated with the Internet in the public mind to the extent that it became the de facto method to reference a website — everyone wanted to be a “dot-com.” The big difference between then and now is Google and other search engines. Few people still type in a domain name when browsing, instead searching for the item of interest and then clicking a found link. This turns out to be very important, because it means you can be much more flexible when deciding on your domain name. The ideal used to be “x.com,” the shortest name possible with the com TLD. Today, something such as “my-incredible-web-site.xyz” is perfectly OK. As a side effect, longer names have their own value. joes-hardware-store.biz is very readable and very easy to type and to speak. I often suggest to clients that they consider longer domain names such as this, with dashes taking the place of spaces. Choose your name carefully, remembering that it will become your brand. Don’t be afraid to think outside the box by using longer names and choosing from the hundreds of TLDs that are now available. About ICANN

For the most part, you will not need to worry about the International Consortium for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). It is the organization charged with managing domain names, including the selection of available TLDs and the accreditation of registrars. Only registrars accredited by ICANN can sell domain names. ICANN is also responsible for enforcing the rules about domain names, increasingly important after the easy way domains were stolen in the early 2000s and the extreme difficulties encountered in recovering them at that time. In most cases, the closest you will get to ICANN will be when your invoice for your domain name indicates that the fee includes a U.S. $0.18 contribution to ICANN. However, you should be aware of ICANN, because you may need its help if there were some sort of dispute regarding your domain name. Because of the stronger rules put in place in the 2000s, that is unlikely, but within the past few years I have used the threat of making a report to ICANN to resolve an issue. Choosing a registrar

All domain name registrars are not created equal. Technically, only ICANN-accredited registrars can issue domain names. However, accredited registrars are allowed to have resellers. In most cases, a transaction with a registrar or one of its resellers will go smoothly, but if a problem arises, it is easier and faster to deal directly with an accredited registrar. Resellers often have fewer resources and less knowledge, making issue resolution more difficult. If you want to know whether a registrar you are considering is accredited, see ICANN’s list. I do not recommend resellers. I also do not recommend acquiring your domain name from your chosen Web-hosting company, because in almost all cases, they are resellers. Not all registrars can lease all TLDs. Before choosing a registrar, use that company’s website to see whether the TLD you want is available. Today, the most common TLDs in a given country are available from most of that country’s registrars, but you still need to check. Also be aware that a reseller may not be able to provide all the TLDs available from its parent registrar. DNS

The Internet operates on numbers known as Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. The reason for domain names is that no one wants to use IP addresses to access websites. One of the key services provided by registrars is connecting a domain name with an IP address so that requests to a website can be routed correctly. This is the role of Domain Name Servers (DNSs) — they are the Web’s telephone directory. The DNS records associated with your website must be stored somewhere. The two most likely locations are with your Web-hosting provider or with your registrar. Usually, the Web host’s DNS system is easier to use, but the registrar’s system is often more flexible. The problem is that the DNS control panels at registrars require more detailed information, which can be confusing. In most cases, I recommend using the Web host, but there are situations in which using the registrar’s panel is more effective. Moving a domain registration from one registrar to another used to be very difficult, dangerous, and subject to loss of a domain. After the scandals of the 2000s and the subsequent rule changes, relocation is less prone to trouble. It can be confusing, though, and getting professional help may be desirable. The process

The suggested course of action is to find a registrar that is accredited, that can issue your desired name, and that has a good control panel for handling DNS. After that, it’s mostly a matter of price. Pricing among registrars is generally consistent, but there are some outliers. Shop around. Ignore any promotional pricing — look at the long-term price and base your decision on it. If that’s acceptable, then by all means take the promotion. Because I recommend purchasing the domain name before obtaining Web hosting, initially there will not be a website connected with your new domain. Registrars will automatically route requests to their own placeholder for your site. That will be your first presence on the Web. It won’t have anything to do with you, but it will be live.

Will Fastie is a Web developer specializing in self-service websites for small businesses. Trained in computer science at Johns Hopkins University, he has held positions as a transaction processing systems programmer, magazine editor, newsletter publisher, Wall Street analyst, CTO, and systems consultant. Shortly after writing this Web Presence series for Woody, he became the editor in chief of this newsletter.

WEB PRESENCE Choosing an email provider: Your biggest decision

By Will Fastie Despite the popularity and widespread use of texting, email remains essential for business communications. Business email is universal, ubiquitous, and not necessarily tied to a specific person or phone number. Its long-form nature, broad capabilities, and nearly automatic communications archiving are unmatched by other forms of correspondence. All of which makes choosing an email provider one of the most important decisions you’ll make when establishing your business’s online presence. Professional appearance matters, and an important branding tool is using your firm’s domain name in your email addresses. Sure, this seems obvious — but some mail services won’t allow it. Here’s what you should know when choosing your email provider. Four ways to set up business email

There are umpteen venues for establishing a business email system, but they mostly fall into the following four categories:

Let’s dispense with a couple of these right off the bat. Just one among millions: It’s tempting to use a free email service. Don’t! They typically require the use of a master domain name — for example, “[my name/business]@gmail.com.” An ISP often has the same limitation — e.g., “[name]@comcast.net.” Reject any service that doesn’t let you use your firm’s domain name as part of the email address. Using an ISP-provided address is especially problematic because it effectively locks you into that company. If, say, you change from Comcast to Verizon, you’ll lose the comcast.net address. The switch will be costly for you and confusing for your customers. It means changing all marketing materials and all online references to your business plus transferring archived email from the old ISP to some other mail service — usually a tricky proposition. Most importantly, there’s no obvious connection between your email address and your brand. DIY email: This is the antithesis of the free email services. Setting up your own email server gives complete control over your email environment. It can also be cost-effective in settings that require a large number of email accounts/addresses (typically, 50 or more) for staff or other purposes. However, small businesses typically don’t have the resources needed to manage their own email system. Supporting an in-house mail system is complicated, to say the least. You should put the server on a separate computer and have a highly reliable Internet connection with a static IP address and sufficient bandwidth. What happens if power to your business fails or the connection to the ISP gets cut? Your entire email system is down until service is restored. You must also be capable of managing email security — a hacked server could be a disaster. In short, a small business can’t expect to match the redundancies, backup capabilities, and security offered by dedicated, outside email services. Web-host services: It can also be tempting to use the mail-hosting services provided by the company that hosts your firm’s website. Most plans offer at least 25 email accounts — more than sufficient for a small business. But email can consume vast amounts of storage space, and website hosts have limits — even those who claim “unlimited” space. You might have to systematically and routinely clean out older email to stay within the storage limits you’re allowed. That can be a problem because your firm’s email represents business documentation. Constantly deleting it is not a good practice. More importantly, if you decide to change ISPs, transferring email to the new host could be costly and complicated. Best option: Third-party email services: I recommend this option to all of my clients for these key reasons:

I recommend budgeting USD $5 per month per email address for a third-party email subscription. Popular services include G Suite (Google), Microsoft 365, Rackspace, and Zoho. But again, there are many others to choose from, as an online search will show. Ancillary email accounts

You now know why a firm’s primary email addresses should include its website’s domain name. But there are some good reasons for setting up one or more email accounts that have a more-anonymous address. And in all cases, I suggest using a free service (e.g., Gmail) for these adjunct accounts — here’s why. First, domain-name ownership is often public information, including personal data such as name, mailing address, phone, and email address. You can purchase “Domain privacy” (more info), but I typically don’t recommend it. Still, you don’t want your primary business addresses to be easily scraped by spammers, identity thieves, and other evildoers. To avoid that problem, use a free account from Google or Microsoft for your domain-ownership information — and don’t use that address for anything else. If it becomes compromised, or it becomes a spam bucket, it won’t affect your normal business communications. Second, you might need a specific email address for obtaining other services. For example, I equip all websites I build with Google Analytics, and that service requires a Gmail account. So I ask my clients to set up a generic account such as “web-services-[mydomain]@gmail.com” and use it exclusively for this purpose. A generic Gmail account is also handy when acquiring paid Google services such as the Maps Platform. The general rule of thumb is to keep ancillary email addresses away from your public Web presence. They are simply an administrative convenience. I think you’ll find that using a third-party email service works best for your small business — once you get accustomed to the monthly charges.

Will Fastie is a Web developer specializing in self-service websites for small businesses. Trained in computer science at Johns Hopkins University, he has held positions as a transaction processing systems programmer, magazine editor, newsletter publisher, Wall Street analyst, CTO, and systems consultant. Shortly after writing this Web Presence series for Woody, he became the editor in chief of this newsletter.

WEB PRESENCE Choosing a web-hosting service: The ins and outs

By Will Fastie The heart of the Web consists of millions of web servers, constantly streaming out trillions of webpages. Relatively speaking, web servers are simple affairs — but choosing whose servers will host your website … not so much. Years ago, a brilliant programmer I know once quipped that he could build a web server with just 12 lines of code. He was probably correct: for an exceptionally simple website, one containing nothing but text-based HTML, serving up pages is nothing more than requesting a file from the server and rendering it in a Web browser. Today’s websites are, of course, far more complex, often written with languages such as PHP, Python, C++, Ruby, and many others. But ultimately, the general principles remain: it’s still an HTML file that’s sent to a local browser. So in theory, anyone with some basic know-how could set up a web server in their home — there are even applications that will build the “stack” for you. But effectively and reliably serving up a website is both time-consuming and complex, involving backup strategies, hardware maintenance, management of IP addresses, and more. All that requires skills and commitment that most individuals and small businesses either lack or don’t have the time for. For those reasons, most of us rely on Web-hosting companies. They have the expertise and resources to reliably deliver webpages, day in and day out — often at a very modest cost. Given their mandate, you might think that most Web-hosting services are alike. Generally speaking, they are; but dig down, and you’ll find that they’re not. Here’s what to consider when choosing who will host your website. Pricing

Website-hosting for small businesses and individuals can be surprisingly inexpensive. Previously in this series, I noted that I pay about USD $6 per month for my account at Pair Networks — and that includes four separate sites, all with SSL certificates. (Update: Pair’s price is now $8 per month, but I’m now hosted elsewhere for USD $13 per month.) But when it comes to the initial hosting fees, it’s important to not take advertised prices at face value. Look carefully at what exactly you’re getting for your money — and what will cost you extra. Most important, remember Will’s mantra: No web service is unlimited, no matter what the company says. Also, watch for “introductory” offers. It’s akin to those cable-company promos (more like scams): that low initial price will probably jump up sharply after the first contractual term expires. I especially abhor this practice with Web-hosting services for two reasons. First, it masks the true, long-term cost of hosting a site, lulling the buyer into assuming that a smaller budget will be the norm. Second, intro offers that span lengthy terms — possibly up to three years — might seem attractive from a budget perspective, but they will lock you to that provider for longer than you might want. Note that you typically pay for these discounted offers up front. And if you move your site to another host for whatever reason, you probably won’t get a full refund. Seventeen years ago, when I started helping clients with their websites, I advocated longer contracts as a way to save money. These days, I encourage paying the slightly higher fee for a month-to-month account. It lets you cancel the service more quickly, minimizing the cost of switching hosts while maximizing flexibility. Features

Most hosting companies offer the same basic set of features in their hosting plans. But the combinations of features and their nature can differ significantly. Here are some of the key features to check out: Control Panel: This is the master online console for your hosted account. You want an especially strong password for accessing your website’s backend controls. cPanel is one of the most popular consoles; GoDaddy, HostGator, and many of the other big-name hosting services use it. Some boutique hosts (such as Pair Networks) have rolled out their own custom control panels. I prefer Pair’s because it’s simpler than cPanel — although it does lack a feature or two. So it’s worth researching the console used by prospective hosts. You’ll have to decide the level of complexity you’re willing to handle. Some hosts will help you get started, but if your website-management skills are minimal, you should also consider consulting help. Domains: Many basic plans allow only one or two domain names — which means only one or two independent websites. My plan says “Unlimited” domains, but keep in mind my mantra: It’s never truly unlimited. For instance, my plan limits me to 15 SQL databases. Because the sites I build require at least one database, my plan effectively limits me to 15 sites. (More on databases in a moment.) One plus of “unlimited” domains is the ability to establish multiple domain names that all point to the same website — helpful, if you’re trying to dominate a brand. Sub-domains: These are sites that are identified by a prefix to a top-level domain name — for example, store.joes-hardware.com. Sub-domains can represent an entirely independent site or a section of the main site. Although my previous Pair plan has “unlimited” sub-domains, many plans set a limit because each sub-domain requires hosting resources. My current plan has a combined limit on domains and sub-domains. Storage: This category requires a little math plus an understanding of how a host’s system works. My plan allows 15GB of total storage. All together, my four sites take up about 2.5GB of space — so I’m nowhere near the limit. On the other hand, my plan sets no limit on the number of files. My four sites consist of roughly 28,000 files — all the code, images, and other material. Doing the math based on an average file size, I could probably store 500,000 files. As they say, your mileage will vary. The cPanel-based hosting plans I’ve worked with are limited to 250,000 nodes. That’s a tricky concept: A node can be an ordinary HTML file, one photo, a single email, and so forth. Over time, emails can suck up a large portion of your node allotment. But that 250K limitation is reasonable if, as I always recommend, your email is hosted elsewhere. Bandwidth: Generally speaking, this represents the allowed amount of data transfers — in bytes — between your hosting server and browsers. As with your phone, it’s the amount of data you’re putting through the pipe each month. Some hosts will specify a bandwidth quota. Other hosts will claim “unlimited” bandwidth but with a hidden catch. A clause typically buried in the service’s terms-of-service agreement prohibits sites that use huge amounts of bandwidth. You’re just not going to get away with setting up your own version of YouTube with a $12-per-month hosting plan. When the host sees heavy, continuous traffic from your site, it’ll threaten to shut you down — or just do so without notification. My recommendations on bandwidth have also changed over the years. Early on, I looked for plans with no limits. But as I’ve gained experience, I’ve found that the quotas attached to economy hosting plans are mostly adequate for small businesses. I tell clients that exceeding bandwidth limits is a nice problem to have — it clearly shows that the site is heavily visited. And that problem is easily solved by simply upgrading the plan. Databases: Again, low-cost plans usually have a limit on the number of databases — and always on the size of those databases (typically 1GB). Based on my experience, around 50MB is the minimum acceptable limit. Note that these size restrictions are based on stored text and numeric data — but not images, which fall under the overall storage-space cap. So make sure the plan’s database quota is sufficient for your sites’ needs. Coding languages: Any website built with a content management system (CMS; e.g., WordPress) requires a back-end programming language. PHP is supported on every hosting plan that’s not designed specifically for some other language. My plan is something of a polyglot, supporting PHP, Python, Ruby Gems, and even Node.js. (WordPress requires PHP.) SSL Certificates: Some years ago, SSL certificates (certs) were an expensive add-on. But with the rising popularity of the nonprofit Let’s Encrypt certification-authority service, many hosts now offer free or very inexpensive certificates. I pay no additional fee for three of my sites, but for the fourth, I pay an extra $10 per year. These days, every website should use SSL for secure connections. The primary difference between free and paid certs is insurance. If the certificate fails to protect the server/browser connection, and you incur losses, the insurance will cover the cost up to a specified limit. Not surprisingly, the higher the limit, the more expensive the certificate. With free certificates, you’re on your own. Bottom line: Don’t purchase a hosting plan that doesn’t offer free or low-cost SSL certificates. User Accounts: Most hosting accounts allow only one user — the account holder. Anyone else working on your site will need to use those same credentials. And that could expose critical business information such as payment methods to someone outside your company. A few hosting plans — most notably, GoDaddy Pro — allow separate credentials for site management but not for the full account. That limited access is granted and can be revoked by the account owner. I really wish all hosting plans had a “consultant” sign-in option. Without it, you must implicitly trust anyone who might work on your website’s back end. Performance: Inexpensive hosting plans use shared servers — your site lives alongside many other sites. With today’s powerful hardware, each physical server might support hundreds or thousands of sites (more info). I’ve found that most hosts make a reasonable effort to balance capacity and performance in order to assure smooth and responsive operation on each website. For technical reasons, databases are not stored on the shared servers, which means that database access is handled over the host’s internal network. That setup can impact data-centric tasks — especially with low-cost hosting plans. I’ve noticed lags in my sites’ performance from time to time. I can live with it for now, but if traffic goes up significantly, I might have to upgrade my plan or move to another host. Growth: Individuals and many small businesses can thrive in economy hosting plans. But of course, more website traffic is always welcome. However, at some point the growth will affect site performance. So before committing to a web host, check out the path to higher-capacity, more-advanced plans — and have a good understanding of what higher fees will buy. Options will include virtual private servers (aka virtual dedicated servers; more info) and dedicated physical servers, both of which will require considerably more technical expertise. With dedicated servers, system management may be entirely on the account-holder’s plate. The Cloud

The most widely known cloud-computing services are Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure. They go way beyond simple website hosting, offering a broad range of advanced IT computing services. But for a rapidly expanding small business, both have the capacity to automatically handle growing site traffic — with no loss in performance. These services are pay-as-you-go: you’re charged for the computer time used by your site, for every byte transmitted over the wire, and for every byte accessed from a database. In other words, you pay only for what you use (at fractions of pennies for each transaction). That means your costs can be unpredictable. Consider cloud services if you know your site will require high capacity and top-notch security, reliability, performance, and management options. Keep in mind that you’ll likely need extensive skills — and if you don’t have them, you’ll need professional assistance.

Will Fastie is a Web developer specializing in self-service websites for small businesses. Trained in computer science at Johns Hopkins University, he has held positions as a transaction processing systems programmer, magazine editor, newsletter publisher, Wall Street analyst, CTO, and systems consultant. Shortly after writing this Web Presence series for Woody, he became the editor in chief of this newsletter.

WEB PRESENCE Building your business website: Understanding the options

By Will Fastie Your company website is the centerpiece for your online presence. It should be welcoming, attractive, and effective. “Well, duh!” you might retort. But it’s amazing how many small-business sites fail at that simple task. So before you (or your consultant) lay down a single line of code for your new site, spend some time to consider its look and function. Done? Now you’re ready to dig into the mechanics of website development. Here are your options. Tools for building websites

In the previous installment of this series on small-business websites, I mentioned that the act of serving up webpages involved little more than sending HTML files from an online server to a local browser. Now it’s time to discuss how those pages are constructed. (Surprisingly, there are only a few ways to build websites.) I’ll also review the pros and cons of common site-construction tools. (Full disclosure: The bio at the end of this article states that I’m a website developer. And as with most developers, I have my particular preferences for how to construct a website — which means I have a slight bias toward one of the methods discussed below. But in order to build sites that are thoroughly tailored to my customers’ needs, I have used all of the following schemes. So I believe I can talk about them objectively.) WYSIWYG editors for simple sites

Many small businesses want nothing more than a modest website that’s easy to maintain. Most of these sites are essentially static — i.e., they’re not interactive and change infrequently. Building this type of website isn’t especially difficult; you can hand-code each webpage — using HTML and hopefully a bit of CSS and JavaScript — with nothing more than simple image and text editors. Keep in mind, however, that HTML/CSS/JavaScript are programming languages; you’ll still need some fundamental coding skills. In the late ’90s, a few applications emerged that allowed website coding with more intuitive WYSIWYG (what-you-see-is-what-you-get) interfaces. You worked in a word processing–like screen, and the app wrote the code in the background. Two notable examples were Microsoft FrontPage (created by Vermeer Technologies) and Adobe Dreamweaver (created by Macromedia). You could also use Microsoft Word (a terrible idea) and Publisher (more sensible but messy in practice). It was a great concept — especially for anyone who did not have the time or interest to learn a programming language. Unfortunately, good WYSIWYG apps designed specifically for building webpages are exceptionally complex — they’re very hard to write and even harder to keep current, due to their integrated browser. In fact, keeping the internal browser up to date was so much work for Microsoft, it dumped FrontPage (by then called Expression Web) in 2012. Only Dreamweaver remains standing. (Dreamweaver’s WYSIWYG format works, but some developers find the code it creates maddening.) So the most popular method of webpage development is a hybrid — using a regular code editor for writing HTML, CSS, and JavaScript (along with other languages) and previewing pages (the “design” view) in a standard browser. Yes, we’re back to hand-coding. I maintain a couple of static websites, including my personal Air Traffic Controller

So I still use EW4 for some simple website development. It’s a shame that it’s no longer supported; Microsoft officially dropped the app on July 14, 2020, and its free download had been removed a month before. Hosted DIY website builder

Many web-hosting companies offer online development apps, typically accessed through the host’s control panel. I call these tools “web builders,” a name also used by some hosting companies. Web hosts provide these apps for two reasons. The first is marketing: web-builder apps are invariably promoted as easy-to-use, do-it-yourself solutions for creating your site. For someone lacking design and coding skills, this can be quite enticing. And it can be a viable option — if your site is basic. Many of these apps include attractive and effective templates to give you a development jump-start. The second goal is to lock you in to that host. Web-builder apps are always proprietary, making it almost impossible to move your site to another hosting service. In some cases, the assets that make up your site can’t be transferred because they remain the property of the host. So if you go the web-builder app route, expect to start over if you move elsewhere. In addition to hosting services that offer web builders and other site-development options, there are services that let you create a site only with their builder tools. A well-known example is WiX.com. The same limitations apply here: your website is based on proprietary tools and assets, making it difficult, if not impossible, to move the site to some other hosting service. Most good web-builder apps let you pick from an extensive library of website templates, which helps keep design costs low. You might have to provide just the text, logo art, and other images as needed. All that said, I’m not fond of the web-builder approach — and here are two examples why. Both these stories involved rescuing businesses from failed DIY attempts. (I’m not suggesting that creating an effective site with web-builder apps is impossible. WiX.com’s tools, for example, have gotten much better since my original experiences with the service.) One of my earliest clients tried WiX and ended up with a wreck of a site. I spent a little time trying to unwind the debacle with the service’s web-builder app, but ultimately the client wanted features WiX could not deliver at the time. (WiX’s marketing material led my client to believe otherwise.) So I ended up building a custom site that runs to this day. I will note that this client is a very smart guy, but building a site is simply not in his wheelhouse. And that’s probably the case for most small businesses. More recently, a client’s previous developer had used GoDaddy’s web-builder app to create a starter site — and it, too, turned into a wreck, despite the alleged simplicity of the page-building tools. I recommended abandoning GoDaddy’s app, but the client was in a rush and asked me to simply clean up the site. I lost money on the deal due to the web-builder app’s cumbersome UI — the project took more than twice as long as expected. I also had to monkey-wrench some things because the builder app couldn’t do exactly what the client wanted. Web-builders are limited by what I call “stacks.” The builder app and its templates have a set repertoire of “blocks” that can be stacked one on top of another. You can create only what’s offered by the blocks. If you don’t like the way the stacked blocks look or work, you’re out of luck. I’ll make one more point about web builders — something that also applies to WordPress. Many so-called website “developers” do not have deep technical skills. That’s because a large number of advertisement, public-relations, and marketing agencies have discovered that it’s more cost-effective to build basic sites with web-builder apps — no special skill set needed. That’s what got my client who used GoDaddy into trouble. Agencies often don’t charge specifically for building the site; they charge a recurring fee for their services. So they have little or no financial incentive to do anything more than deliver the minimal solution that meets the client’s specs — and in many cases, the agencies hold sway over those specs Working with the WordPress platform

When one of my clients requires a templated web-builder approach, I invariably point them to WordPress. Why?

Originally, WordPress was intended for simple online publishing — one of the early self-service blogging systems. But over the years, it has evolved into a powerful content-management platform. In short, it’s far more extensible and flexible than the block-stacking web-builder apps. WordPress’s ability to serve media — images, video, audio, and document files (Word, Excel, PDF, etc.) — is exceptional. Moreover, the back-end user interface has improved over the years, making it much easier to use, especially for those who lack extensive coding skills. With some basic WordPress knowledge, almost anyone within your company can use the platform effectively. All that has made WordPress very successful; Wikipedia states that there are 60 million WordPress sites worldwide. WordPress cons: During the development phase, finding that perfect extension can be challenging, even when you pay for it. My brother tried three ecommerce extensions before giving up on WordPress. (While he misses some WordPress features, he’s reasonably happy with his current custom-website solution.) Also, writing a custom extension is often complex and expensive. Even the simplest functions, quickly written for a custom website, will take time and skill to create as a WordPress extension. And that will increase your cost. A further complication is the pervasive “mobile” landscape — which is no longer landscape. Okay, that’s a bad joke. Still, almost everyone uses their phones for Web activities … and they typically do so with the device held vertically in portrait mode. That’s given rise to the so-called “responsive” website design concept: sites that automatically reformat themselves to match a device’s screen size and orientation. In other words, the better websites have become “mobile-friendly.” But building a responsive website isn’t easy, and as a consequence, a huge number of contemporary WordPress templates look and behave in a depressingly similar way. Good design and branding have gone out the window. Bottom line: If you’re uncomfortable hiring a custom-website developer, WordPress is the next best choice. Building a custom website

It’s important to understand what I mean by “custom.” It doesn’t mean designing and coding entirely from scratch for every new site. Many developers, myself included, have extensive stocks of back-end code (about 30,000 lines worth, in my case) that they can quickly apply for site design, content, and functionality. In other words, they have their own specialized content-management systems. Custom-site developers also have the tools and methods for building out websites quickly and efficiently. Custom sites have almost no restrictions on what the public-facing side looks like or how the back-end functions. Moreover, the site can be tailored to fit the exact needs of the client. Here’s a really simple example. I do a lot of reading, but I have trouble remembering whether I’ve already read a book or it’s still on my wish list. So I quickly built an extension for my personal site that manages my “library.” I then built a webpage (Figure 2) that’s visible from any browser, including on my phone. Best of all, it’s private: search engines are blocked, and the general public never sees it. I don’t know of a single web-builder app that can do this. There might be some sort of WordPress extension for this task, but it surely won’t work in my preferred style.

With a custom site, you can get exactly the online presence you’re looking for: a perfectly branded design that’s completely self-service. Here are some considerations, both pro and con:

Summary: These are the main ways websites are built. I hope this brief guide will help you make the best choice for your situation.

Will Fastie is a Web developer specializing in self-service websites for small businesses. Trained in computer science at Johns Hopkins University, he has held positions as a transaction processing systems programmer, magazine editor, newsletter publisher, Wall Street analyst, CTO, and systems consultant. Shortly after writing this Web Presence series for Woody, he became the editor in chief of this newsletter.

WEB PRESENCE Working with search engines

By Will Fastie Leveraging Web-based services is an essential part of building an effective online presence — and search engines are a top priority. In my previous installment, I stated that this article would focus on social networks, which are also important for your online business persona. I’d intended to include some information on search engines, but during the research and writing process, I realized there was more to say about search. So the next column will cover social networks — I promise. One of the buzz words constantly thrown about when discussing online searches is SEO, short for “search-engine optimization.” I’ll state right from the start that I’m dubious about the value of current SEO practices — and practitioners. As you’ll see, much of the following information includes that point of view. What you should know about search engines

For much of the English-speaking world, the two search-engine behemoths are Google and Bing. But in practice, only Google requires your attention. Far more than a ubiquitous verb for finding stuff online, Google provides many features and services that can benefit your business website. Bing used to offer similar features but appears to be taking a different approach these days. In any case, if you follow Google’s content guidelines, your presence on Bing will be fruitful as well. There’s no deep magic to SEO. And despite what the so-called experts will claim, there are really no clever tricks that will influence your Google placement. But there are some steps you can take to make your site more “search-friendly.” It starts with content. Long ago, Google’s documentation stressed this point, stating that a search-valuable webpage should have at least 400 words. I’ve preached this doctrine to my clients for years, and it’s proved valid: the more textual content a page contains, the better it will perform in searches. That includes such stock pages as “Home” and “About Us.” More recently, it’s become clear that both Google and Bing analyze sites semantically — as opposed to just counting keywords. This is an important concept. The quality and specificity of a webpage will drive a search engine’s estimation of relevance in a given search. Bottom line: I tell my clients that “content is king” — and I believe it’s Google’s mantra, too. What does semantic analysis mean? Let’s say you’re in the swimming-pool construction and service business. Your website needs to contain plenty of informative content on that specific business. Any information that’s not related to swimming pools isn’t going to help you with searches. Industry-specific topics, language, and jargon make all the difference in attracting search engines. The goal is to make search-engine algorithms conclude the equivalent of “Wow! This site must be a swimming-pool business!” If the search service doesn’t make that connection, the algorithms will return an ambiguous result. In which case, when someone enters a search for “swimming pool companies in my area,” your business may be well down the search-results list. Again, content is king — but only if it’s relatively detailed and abundant, and highly relevant to what you do. Google Analytics: I recommend that all small businesses sign up for Google Analytics. Its primary value is in helping you track who’s using your site, where they’re located, and what information they’re viewing. But there is a lesser-known reason for using Analytics: the collected data are used by Google Search. That harvested information is put into Google’s “dossier” about your site — and that’s a good thing. It makes for better search performance. SEO services: As mentioned, I’m a curmudgeon about paying for search optimization assistance that claims to extend your business’s online reach. In fact, I believe that SEO is something of a scam. My reason is simple: I’ve yet to see a suitable return on the SEO investment. Many search-optimization consultants charge a monthly fee, and it can be higher than all other hosting costs combined. I’ve had to jump in and help several clients with optimizing searches. I made some adjustments to their site content, making it relevant, and convinced them to drop their paid SEO “consultants.” I’ve yet to see a decline in their search presence. Here’s the main point I make to my clients: SEO “experts” typically claim that they can manipulate your site in ways that will attract more search-engine attention. But Google has possibly thousands of programmers who spend their time tweaking search algorithms so that the system can’t be “deked.” I think it’s highly unlikely that a typical SEO consultant can out-smart Google. In short, I’ll continue to push my quality-content mantra because it works with the Google Search system. Advertising: If you’ve tweaked your content but are still not satisfied with search results for your site, another option is to buy advertising. Ads improve search results in two ways: first, ads are typically placed at or near the top of the organic query results (the results not related to ads). Second, clicks on ads feed back into the search-engine algorithms and improve the organic search results. SSL: Most Web browsers use a small “padlock” icon to indicate SSL-certificate protection (i.e., HTTPS instead of HTTP). But a few years ago, Google Chrome added a more aggressive approach to security by displaying a “not secure” tag next to the URL of sites lacking SSL. This was a tectonic change for businesses. Who would want their site flagged as potentially dangerous? Google has also taken a further step: if a site does not include SSL protection, it loses points in search results. Bottom line: Every business needs an SSL certificate — and it’s why I recommend hosting companies that offer free certs. Mobile-friendly: Google says it devalues sites that it deems unfriendly to mobile devices — specifically, smartphones. “Unfriendly” means that the site is not designed to display well in a small-screen format. That includes pages that have excessive load times (aka wire weight) and/or are too long. The knock on wire weight was apparent when Google first made the change, but it’s less of an issue today because of better bandwidth in the mobile space. Lightweight pages are always good, but there’s no way Amazon (or even Gmail) can be considered “slender.” “Designed for mobile” is controversial because Google is in the phone business; it supplies both the OS (Android) and the hardware (Google Pixel). So mobile-friendly sites are, in theory, good for Google as well. In practice, it’s a bit more complicated. The business sites I’ve built for clients are not what Google defines as mobile-friendly, yet most of them get good search results and work acceptably well on small devices, even when they’re not specifically designed for it. In other words, I’ve seen no evidence that sites are being penalized — despite robo-mail from Google warning that the sites aren’t up to snuff. Sitemaps: A website’s sitemap is an XML file that helps search-engine Web crawlers obtain useful information about what’s on the site (more info). With Google, you can speed up the process by using the Google Search Console; the map’s contents will be added to your site’s dossier. Here’s the sitemap for one of my sites:

This file does not list all pages on my site — just those I deem important. (Search-engine Web crawlers will eventually find all the pages in the site.) I consider sitemaps so important that I make it easy for clients to reconfigure them at will. Time: Your site isn’t going to garner search-engine attention immediately. It can take months for a site to make its way up the list in search results. We’ve become accustomed to instant gratification in our digital lives, but this is a case where patience wins out. Fortunately, that relatively slow churn means that advances you make toward getting to the top of search results will stick for a while. In other words: once found, your site is unlikely to drop off the radar. Do these techniques work?

Yeah … they do. Let’s look at some examples. As a hobby, I keep a list of banjo makers on my site. I’ve maintained it in one form or another for over a decade. I’ve done nothing special to promote the page, except to include it in my website’s sitemap. If you search for “banjo makers” in either Google or Bing, my site will typically be at the top of the results list — right after the ads, of course. Here’s Bing:

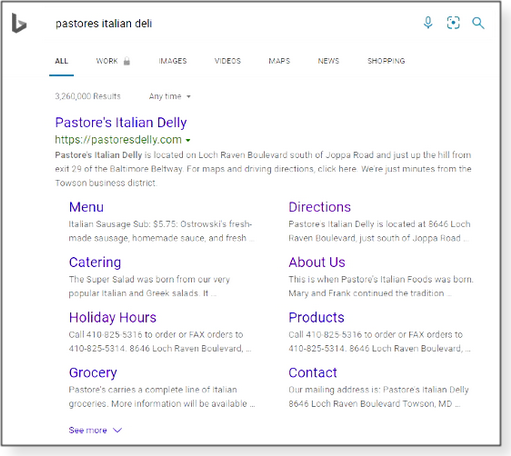

So why am I getting top billing when I haven’t done anything special? In the case of Google, it’s mostly because the site’s Google Analytics data is telling the search engine that the page has good content and is frequently being visited by folks looking for banjo makers. No highly paid SEO consultants needed, just common sense and patience. How Bing gets that info is a mystery to me. But it does … and it can’t be by accident. Not surprisingly, search-engine algorithms try to make top-of-the-list results useful and interesting. For example, Figure 3 shows the search result for one of my clients, Pastore’s Italian Delly.

Again, the excellent search results can only be due to the use of a sitemap and Google Analytics. Pastore’s didn’t pay for this placement or the detailed information — it was entirely organic. The above Bing screenshots reinforce the value of sitemaps. I assume it doesn’t collect the same level of data as Google Analytics, yet it still put the Pastore’s page high in the results. In Figure 3, you’ll also notice that I misspelled the name of the business in the search. Decades ago, the owner decided to use the word “Delly” instead of the more common “deli” in order to set himself apart from the competition. I searched using deli and still found the business. (Your results may vary due to location.) Pay attention to search

Enhancing your search results is critical because it’s one of the primary tools we all use for finding businesses online. As the site owner, it’s important to understand the role of search engines in building your Web presence. You really do want to stay on the good side of Google and Bing. Do the basics well and avoid falling for SEO snake oil, and search will be your friend.

Will Fastie is a Web developer specializing in self-service websites for small businesses. Trained in computer science at Johns Hopkins University, he has held positions as a transaction processing systems programmer, magazine editor, newsletter publisher, Wall Street analyst, CTO, and systems consultant. Shortly after writing this Web Presence series for Woody, he became the editor in chief of this newsletter.

WEB PRESENCE Business social networking

By Will Fastie The major-league social networks such as Facebook and Twitter can be a big help in establishing your company’s persona on the Web — but often at a cost. I have an instructive tale about Facebook. The story is a bit dated, and hopefully the world’s mightiest social network has improved somewhat, but it will give you a small perspective into the intricacies of social networking — and the sorts of trouble they can pose. I’ll say upfront that I never wanted to engage in social networking. But that’s not a good look for a Web developer, so I established accounts everywhere. However, to limit actual “networking,” I provided minimal information about myself. Later, as I needed to better understand Facebook, I added quite a bit more substance to my profile. That included entering my marital status (for 30 years now; it’s not exactly news) into what had been an empty profile item. Starting the next day, I received dozens of congratulatory messages — mostly from people I had known for years. Why did this happen? Basically, Facebook made a bad (or badly calculated) guess. Instead of notifying others in my network that I’d added new information to my profile, Facebook decided that my marital status had “changed” to married. It took a couple of weeks for that brouhaha to die down, and most of my correspondents were quite bewildered by the event. But I think it gave us all a bit of insight. In short, we’re at the mercy of algorithms that are mostly invisible to us. We accept a social network’s terms of service because we must in order to participate — but along with that acceptance, we should be demanding full disclosure. Here’s the bottom line: Before engaging with a social network, spend some time researching just what you’re getting into. Consult friends, family, and business associates who have been using the services. As best you can, you want to understand the possible benefits and consequences. It’s all too easy for things to go wrong with social networking. You might inadvertently put off potential customers and clients, or you might become the target of mischief. Whatever the reason, getting out of a social network can be harder than you think. Tip: Keep your personal and business social-networking accounts completely separate. General observations on social networking for business

Top benefit: Regardless of the size of your business, social networking opens up a vast audience. It can be especially effective for small companies with limited advertising resources. Top shortcoming: Social networks can be a time sinkhole that’s difficult to climb out of. To be effective, social networking will require a constant and consistent commitment. Lurking trouble: The most difficult issue surrounding social networks is defining them. Are they platforms or publishers? Are they bastions of free speech or are they censors of content? Currently, it’s in the best interest of Facebook et al. to play both sides, using whichever set of rules is most convenient at the moment. And that has drawn calls from users, politicians, and governments for some sort of regulation. The inconsistent application of these “rules” has also impacted participating businesses — for example, the alarming YouTube “de-monetization” controversy (more info). With rules that are vague and in flux, we simply don’t know what effect future changes will have on how small businesses engage their target communities. For now, simply recognize that these problems exist, that they’re complicated, and that factors beyond your control might have unintended consequences on your use of social networks. The major players

Twitter: Its immediacy and brevity make it a good tool for crisis management and damage control. Surprisingly, Twitter has been cited in various business case studies for its efficacious use when things go bad. These studies pointed out that while the press was stressing the negatives, companies relied on Twitter to get information directly to customers, suppliers, retailers, and consumers. Businesses that were open and direct in their tweets generally had good outcomes when the crisis was over. Using traditional communications channels such as email and public-relations services was far less effective. In some cases, bad events have resulted in a rapidly escalating Twitter storm. That’s not the time to try to learn the fine points of Twitter. Just as you should don a lifejacket before falling overboard, you’ll want to have a good working knowledge of the service before a crisis arises. Ultimately, you’ll have to decide whether it’s worth the investment in time to build and keep that following. Instagram: Best for imagery — the Twitter for visuals. Instagram makes posting images from phones trivial. Visual records of events can be online in seconds, with little or no preprocessing. (The service now supports videos.) Whether this is good for business engagement is still an open question. It can be too easy to upload images before considering the consequences. Facebook: Best for general conversation. I usually tell my small-business clients to avoid blogs. Keeping a blog fresh with new information and moderating comments can soak up an excessive amount of time. But if a client insists on this sort of interaction, I recommend Facebook. The service’s automated moderation tools take some of the load off the business. Facebook can also be effective for marketing campaigns and non-profit fundraising. For the best results, hire a Facebook specialist — someone who really knows how to work all the behind-the-curtain dials and levers. The service supports video, but there’s a much better option. YouTube: Excellent for video-based marketing, support, and tutorials. I consider YouTube the most potent social network on the planet. Why? You probably already know the answer. Live-action images are often powerful and compelling. And YouTube’s vast and diverse content makes it addicting. Because it’s owned by Google, its search technology is deeply integrated — and the results end up in general searches outside of YouTube. Video should make up a significant part of any small business’s online presence. The drawback of video in general (not just with YouTube) is that it’s time-consuming to produce. Collecting the content requires planning and setup, shooting the video takes significant time, and creating the final output requires a working knowledge of video editing — assembling clips, adding titles and special effects, etc. Video professionals will tell you that they plan on at least one hour of processing for every minute of finished content. That makes video far more expensive than still images. If you do it yourself, you need stuff: cameras, lights, accessories, editing software, and a relatively fast computer. You’ll also have to invest the time in discovering what makes an effective video for your business and how to make the best use of YouTube. LinkedIn: Good for business-to-business engagement and recruiting. Launched in 2003, LinkedIn has stayed true to its original concept: building networks among business professionals of all stripes. However, most of its recent initiatives seem more focused on enterprise users than on small businesses. My LinkedIn account contains virtually no personal information — but almost everything about my career. I think that’s the way most members like it. Whether LinkedIn is valuable to a small company depends on the nature of the business. It probably won’t help the online presence of the local hardware store, but it could be crucial to someone in, say, environmental consulting. Using online “feeds”

All services mentioned above offer the ability to embed network-based content within a business’s site. The content is live: as something changes at the network, it’s reflected in the feed on your website. Setting up a feed with some social networks is complicated — for YouTube, it’s simplicity itself. Small businesses should consider setting up feeds for two reasons. First, the feed puts fresh content on your site, which will help keep visitors’ attention focused on you. In other words, it’s better that they watch a video on your site than on YouTube. Second, feeds can drive traffic back to your site. When posting videos to YouTube, enter a description for the video and include links back to the business’s website. In fact, I’ll suggest that setting up feeds from YouTube is essential. As we all know, YouTube can be extremely distracting and addicting. Watching one video will often lead to viewing several more — and probably none of them is related to your business. Keep in mind that YouTube is designed to hold your attention. You don’t want your customers/clients drifting away into hours of cat videos. Keeping visitors on your site has another benefit: using your Google Analytics results to track what they’re looking at. It’s considerably easier than looking at the tracking data provided by social-networking services — although checking that information periodically can be worthwhile. Note that there are limits to keeping visitors’ attention. Business websites shouldn’t use any design or programming tricks that make leaving the site difficult — for example, making the browser “back” button stick to the current page (as some Microsoft sites seem to do). Annoying your visitors isn’t going to win you points. “Passive” networks

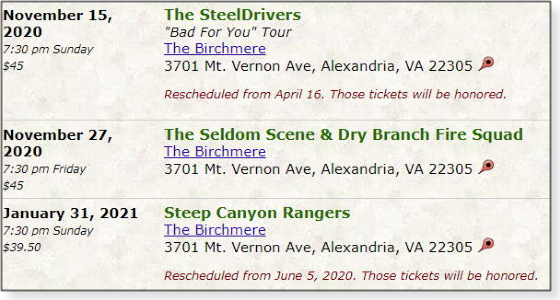

There’s a category of websites that act like social networks — but you have no control over them. These are the so-called “independent” reviews-and-ratings sites. If you get good ratings, your business will benefit. But if you get bad ratings, there’s often little you can do about them. It can be difficult to get bogus reviews expunged, and there appears to be little or no review moderation on these sites. Unhappy customers can say pretty much whatever they want. Here’s one example that hit close to home. My dentist received a bad review — not for poor dentistry work, but because the poster didn’t pay the bill and ended up in collections. It took two years to get this retaliatory review removed. The upside: Most “passive” social networks are huge and thus draw lots of search-engine attention. If you read the previous installment of this series, you might recall the Bing search-results screenshot for one of my clients. That image showed only the left-hand side of the screen. Here’s the right side:

The search results for “pastores italian deli” include a large sidebar full of info from passive social networks. But the big “Website” and “Menu” buttons point directly back to Pastore’s website! This is terrific exposure for a business, and it’s completely organic — in this case, neither I nor my client did anything to make it happen. The client does do some engagement on Facebook, but that’s it. Bottom line: It’s easy to sign up for and use social networks. But to protect your business, it’s important to observe, plan, and execute the process with careful attention. Any problems that arise can quickly negate the hoped-for benefits — and they can be hard to escape. Moreover, the regulatory uncertainty of social-networking services also calls for caution.

Will Fastie is a Web developer specializing in self-service websites for small businesses. Trained in computer science at Johns Hopkins University, he has held positions as a transaction processing systems programmer, magazine editor, newsletter publisher, Wall Street analyst, CTO, and systems consultant. Shortly after writing this Web Presence series for Woody, he became the editor in chief of this newsletter.

WEB PRESENCE Currency, continuity, and commitment

By Will Fastie So your website is now up and open for business? That doesn’t mean you can just walk away. In previous installments of this series, I stressed the important basics of ensuring your site can be easily found. For example, in the “Working with search engines” installment, I discussed understanding the Google search engine. What I didn’t mention was that search engines take into account a site’s age. In short, if your site isn’t considered current, its perceived value will drop, and it’ll fall lower in search-result lists. The answer to that problem is simple (which should, in theory, make this a very short article): To keep up your site’s perceived “currency,” just keep adding and updating content. Search engines notice whether the content of a given page has changed since the last time they looked — and whether they must update their indexes to account for the change. Search engines will also note when that change was made, in effect keeping a chronological record of what has been happening on the site. New website pages are especially important to search engines because the change indicates a significant amount of new content. On the other hand, simple changes to an existing page, such as updating an item’s price or description, or correcting grammar or spelling, are of minor interest. A new page, post, article, or product is simply more compelling. Bottom line: If content is king, new content keeps him on the throne. Tip: If a client’s site is relatively static, I use one little trick to at least suggest currency. My code automatically updates the copyright year at midnight every New Year’s Eve (see Figure 1). That’s important because a current copyright date signifies that the site is actively updated. Who’s going to trust a website with a two-year-old copyright?

Legally, a copyright statement isn’t needed. And if a date is listed, it should reflect significant changes to a site. It’s rare, but a few clients don’t make any changes to their online pages in a given year. Automatically updating their copyright date isn’t likely to raise any legal fuss. There’s a technical aspect to posting copyrights: it works only if the search engine or web-crawling bot sees text. When my backend code generates the dates, it does so on the server, not in the browser. That means the date is straight text when it’s displayed in a browser window. If you use, say, JavaScript to automatically change the copyright date on an otherwise static page, search engines/bots will see JavaScript code instead of text — and the copyright date will be ignored. Keeping copyright dates current is something of a challenge on WordPress-based sites. If you rely just on native WordPress features, you’ll have to maintain the copyright manually. Automating the process requires additional code. I’ve run across some WordPress deployments that use JavaScript, but, again, the copyright date won’t be seen by search engines. Static sites

Some small businesses may not have the time, resources, or desire to aggressively pursue site currency. They tend to view the website as marketing collateral, akin to printed brochures that are never updated — sometimes, over years. Their priority is simply to show basic company and contact information online and to have a Web address for business cards and stationery (yes, business cards are still used). These days, most businesses know that some sort of website is required. It’s a necessary form of validation. There is nothing wrong with static sites for some types of businesses. For example, legal and accounting firms might need to update their sites only when there are staff changes. Confidentiality and privacy requirements limit what they can put up online. I’ve contacted law firms whose sites clearly needed renovating — and they simply weren’t interested. Fortunately, there are ways for static sites to stand tall in searches. For example, “near me” search results are initially based on geography and targeted category (e.g., “law firms”). Other considerations are secondary. So, although a static site doesn’t benefit from a “currency” stance, it’ll still show up in search lists — somewhere. Bottom line: The value of appearing current is relative. It comes down to the nature of the business. The cost of “content”

Static websites aside: for most businesses, appearing current is critical and, again, new content is the key to success. Regular site changes assure continuity: the sense that the site is actively maintained for the benefit of current and potential customers. But new content comes at a significant cost — in time, in creativity, and in attention to detail. No matter what their resources, I advise clients to make some effort to update their sites regularly. And I try to practice what I preach! As I’ve noted in previous articles, I maintain an online list of banjo manufacturers. Left alone, the site gets a modicum of attention. To keep it current and interesting, I update the list at least once a year. (Banjo builders don’t come and go every day!) But I also maintain a calendar of local Bluegrass concerts and festivals in my area (see Figure 2) that’s refreshed about once a month (and more frequently when appropriate — though not so much during a pandemic). This is fertile content for searches because it contains current and future dates.