In this issue PUBLIC DEFENDER: Anom: A $2,000 smartphone that let the FBI listen in Additional articles in the PLUS issue LANGALIST: Short Takes: Three interesting reader-submitted Q&As HARDWARE: Why Wi-Fi 6, aka 802.11ax, for Your Wireless? BEST UTILITIES: Freeware Spotlight — Notes Keeper ON SECURITY: Getting rid of local administrators

PUBLIC DEFENDER Anom: A $2,000 smartphone that let the FBI listen in

By Brian Livingston Special smartphones that were supposedly the most super-secretive in the world actually resulted in at least 800 arrests, the seizure of eight tons of cocaine, and the recovery of $48 million in currency from organized-crime gangs on June 6 and 7. The FBI, Europol, Australian Federal Police, and the law-enforcement agencies of several other countries announced on June 8 that they had quietly intercepted 27 million messages from what’s being called “WhatsApp for criminals.” How this sting operated holds valuable information for you and any company you work for, even if you aren’t planning to join an organized-crime syndicate soon. The phones criminals thought were safe actually divulged everything

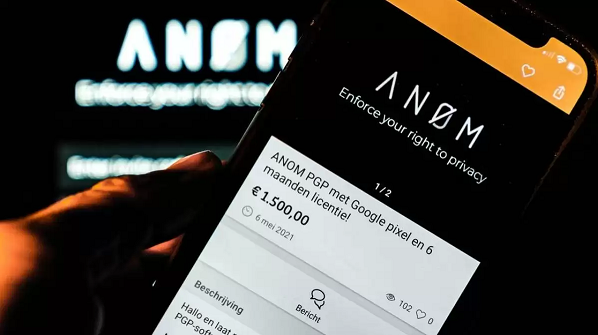

The intercepted material had come from customized smartphones called Anom (short for anonymity). The phones had been “jailbroken” — an ironic term, in this case — with most tracking and app functionality removed. Even the phones’ GPS capabilities were disabled, supposedly to prevent a user’s location from being revealed. (See Figure 1.) To appear like an ordinary phone, the stripped-down devices included a typical calculator app. But the cute utility hid a texting service that was advertised as being untraceable by authorities.

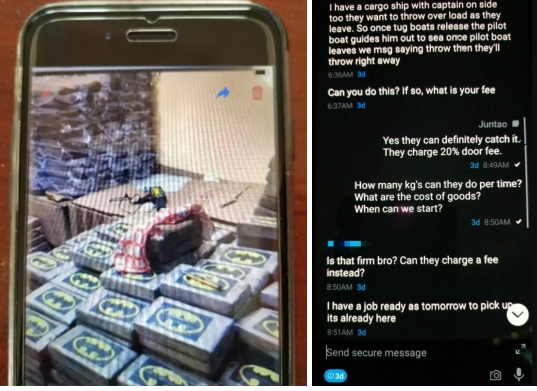

Impressed by the device’s supposedly unbreakable encryption, thousands of Anom purchasers soon dispensed with code words and cryptic comments. Some of the communicators were so bold as to include photos of drug shipments as proof of delivery. And others casually discussed which functionaries who had outlived their usefulness would be whacked or, in one case, thrown overboard to drown at sea. (See Figure 2.) Because the FBI and other agencies had set up the Anom system in the first place, all the messages went straight into law-enforcement computers, where they were translated when necessary and acted upon almost in real time.

To give criminals a good reason to buy the new “super encryption” phones, authorities in numerous countries coordinated their efforts to shut down pre-existing devices and services that also served organized crime:

The shutdown of each of these messaging networks tended to push organized-crime gangs toward a new device — Anom. What the criminals didn’t know is that Anom had been secretly run since 2019 by law-enforcement agencies in the US, UK, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and other countries. Instead of learning a valuable lesson — encrypted phones might not be as secure as advertised — criminals simply flowed into Anom. By May 2021, more than 12,000 Anom phones were operating in at least 100 countries around the world. The Feds even recovered 85% of the bitcoins from scammers

In an unrelated case — but another sign that everything is not as secure for criminals as they may think — the FBI made a major breakthrough in the tracking of bitcoins that had been paid out by a victim of a ransomware attack.

Remarkably, the FBI reported on June 7 that it had recovered 63.7 (or 85%) of the bitcoins that Colonial had sent to the hackers. The agency had somehow determined the perpetrators’ “private key” and simply transferred the cryptocurrency back to the pipeline’s owners. In other words, the FBI had hacked the hackers. What we can take away from these victories over criminals

Anom’s busts and Colonial’s bitcoins have been widely reported elsewhere, so I won’t go into all the fascinating details here. What’s important — for individuals as well as company executives who are concerned about security — is to answer some pressing questions:

What encryption devices can you trust? You can’t fully trust anything. No matter how strong an encryption scheme may be, there’s always a possibility that the software or hardware contains a “back door” to allow some agency — or a snoopy insider — to record your communications. We’ll debate for the rest of our lives the correct balance between absolute privacy, in which no wrongdoing can ever be detected, and legitimate court-authorized warrants to permit agencies to collect evidence on suspected criminals. In the meantime, no matter how much you think you’ve ensured privacy, you always need to consider the likelihood that someone, somewhere, might be listening in.

The PUBLIC DEFENDER column is Brian Livingston’s campaign to give you consumer protection from tech. If it’s irritating you, and it has an “on” switch, he’ll take the case! Brian is a successful dot-com entrepreneur, author or co-author of 11 Windows Secrets books, and author of the new book Muscular Portfolios. Get his free monthly newsletter.

You’re welcome to share! Do you know someone who would benefit from the information in this newsletter? Feel free to forward it to them. And encourage them to subscribe via our online signup form — it’s completely free!

Publisher: AskWoody Tech LLC (sb@askwoody.com); editor: Will Fastie (editor@askwoody.com). Trademarks: Microsoft and Windows are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. AskWoody, Windows Secrets Newsletter, WindowsSecrets.com, WinFind, Windows Gizmos, Security Baseline, Perimeter Scan, Wacky Web Week, the Windows Secrets Logo Design (W, S or road, and Star), and the slogan Everything Microsoft Forgot to Mention all are trademarks and service marks of AskWoody Tech LLC. All other marks are the trademarks or service marks of their respective owners. Your subscription:

Copyright © 2021 AskWoody Tech LLC, All rights reserved. |

Colonial Pipeline, a distributor of almost half of the gasoline and jet fuel delivered to markets in the eastern United States, announced on May 7 that its computer systems had been locked up by a cyber attack. As filling stations in numerous states quickly began running out of fuel, the company transmitted into a hacker’s digital wallet a ransom of 75 bitcoins, worth about $4.3 million at the time.

Colonial Pipeline, a distributor of almost half of the gasoline and jet fuel delivered to markets in the eastern United States, announced on May 7 that its computer systems had been locked up by a cyber attack. As filling stations in numerous states quickly began running out of fuel, the company transmitted into a hacker’s digital wallet a ransom of 75 bitcoins, worth about $4.3 million at the time.