AKB4000010: A Guide to Archiving RedBook Standard Audio CD’s

By @netdef

Published July 8th, 2020 | Rev: 1.0

Disclaimer:

I am not a lawyer, but here’s my non-lawyer-speak personal understanding of how the law in the United States treats copying music CD’s you own. (I might be wrong. You should not take my word for it.)Let us assume you are making personal copies of Compact Disks that you own to play on personal devices for yourself. You must possess the originals to legally keep your archival copies. If you don’t have the originals anymore you are expected to delete your copies. Excuses like bags-o-holding disappearing are not acceptable defenses.

Don’t pirate music; don’t loan or share your originals (after making copies) and especially don’t upload or share the copies themselves. Don’t give away or sell the original CD’s afterwards – but store them in a cool, dark, dry place. Don’t borrow CD’s, rip copies of them, and return the originals to your friends. Don’t ask your friends for copies of their music that they archived. Don’t download music other people ripped for their personal use. You get the idea by now. The legal version of the above says the same thing succinctly in twenty-two chapters using seven syllable words. More info: https://www.riaa.com/resources-learning/about-piracy/

Introduction:

CD ripping: Making a digital archival or backup copy from a music CD to a file on a computer.

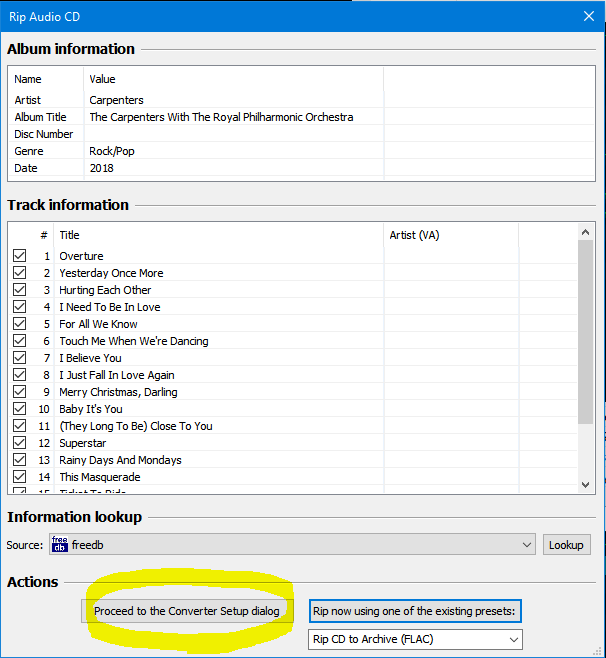

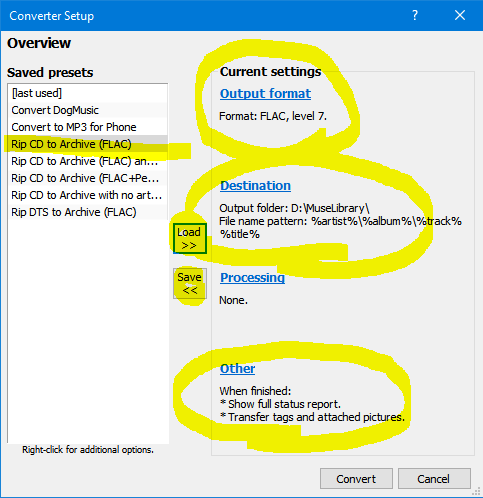

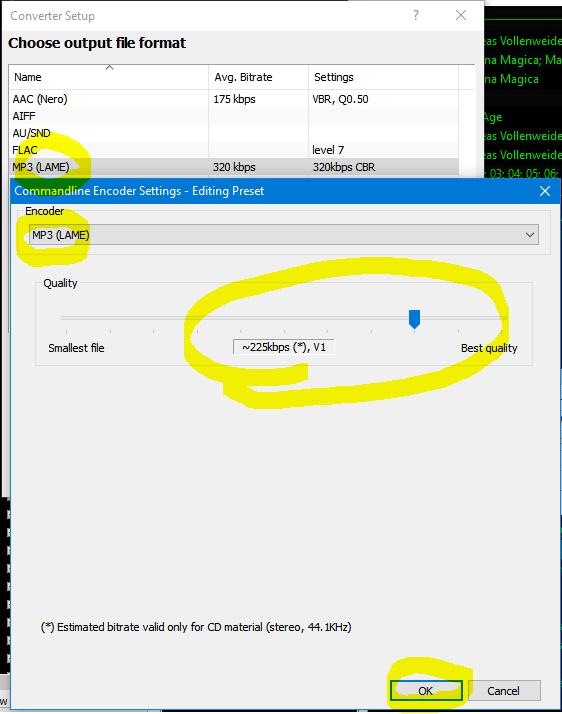

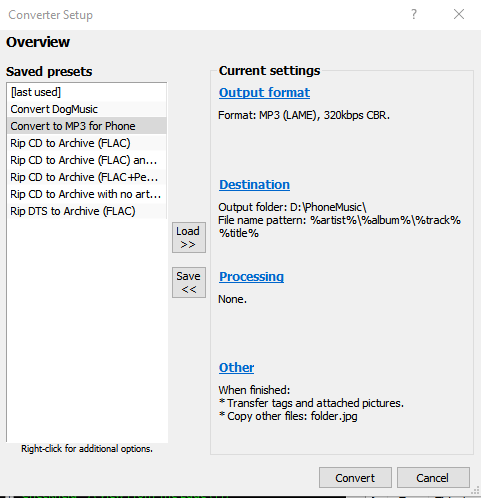

We want to do this right the first time so we don’t have to do it again in the future. (It’s a lot of work!) To that purpose, I will show you how to use an open-source format (FLAC) that is an exact copy of the original, to use a work-flow process to keep these files manageable, and to use automated open-source data tools (music tag services) to make light work of what many fear most: making sure the filenames of the music files make sense. We are also going to use free open-source tools to rip the CD’s, and to encode them into the formats we want.

Q: What is, and why do we use, FLAC?

A: FLAC stands for Free Lossless Audio Codec. It’s a free to use open source music file format. We use it because it’s widely compatible with most advanced music players, and because it’s a true bit for bit copy that can be safely used if we need to convert to other formats. It’s compressed like a ZIP file but can be read and played directly by player software and devices.

More info: https://xiph.org/flac/

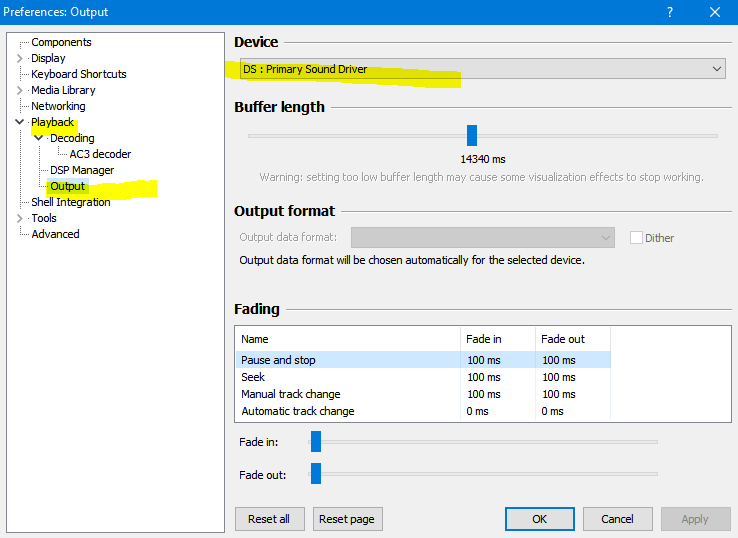

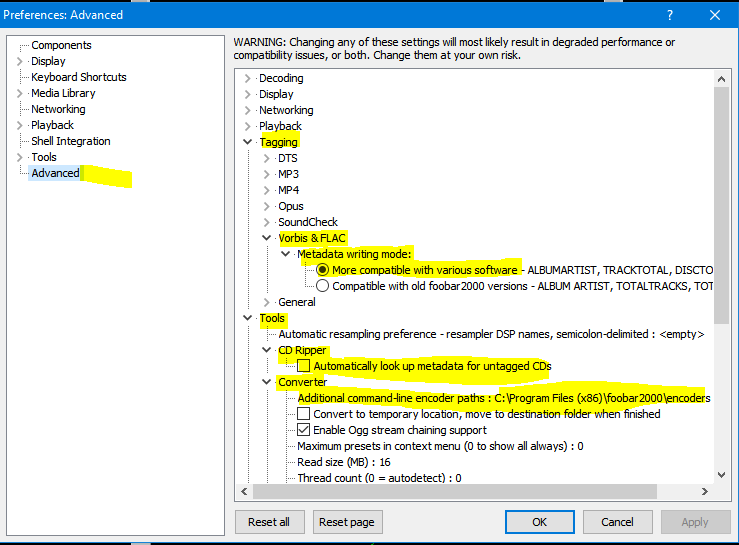

We’re also going to use a free open-source program called FooBar2000. Its UI is a little dated, but it has been maintained very well over the years, is still under active development, is a fully mature product, is very efficient at the job we are going to do and has excellent metadata mass tagging abilities which will help us keep our music organized. It also automates information gathering so we don’t have to manually type in all the titles we want for our music. Our filenames will be created automatically with friendly names like the track number and title, so when we see it on our hard-drive we know exactly what it is. Our music will be automatically organized – as we rip it – into directories/subfolders which will be created automatically with the Artists names, followed by the Album names. As you can imagine, this is a huge labor savings right there, and helps to ensure consistency in our library.

Q: What’s Metadata?

A: Sometimes also called “tags” – it’s nothing more than descriptive information – mostly text – that describes things about your music.

Information like the album name, track title, track number, artists name, the year it was recorded, the musical genre – and optionally much more. The system we are going to use is highly customizable, but we also want to be organized and use the same pattern of descriptions for every single track we archive. (Otherwise we can’t sort and find stuff easily.)This set of descriptions is embedded directly into each music file – so you don’t have to keep track of the information in separate databases. It’s also compatible with pretty much all music software and hardware playback devices. You be able to see what’s playing, what track it is, and lots of other helpful information in the UI of the gadget you’re using to listen to your music.

Legitimate reasons to archive:

1) You’ll have a copy in case of damage to the originals that renders them unplayable.

2) You want to listen to your music on your modern personal devices, in your car from a USB storage device, or via in-house speakers that play from a central storage system on your property. (These are generally accepted safe use-cases but have not, as far as I know, all been tested in court.)

Benefits to the methods in this tutorial:

1) Your copy will be (barring a bad rip) as good as the original source.

2) Your copy can be converted to less strict formats for compatibility with your other devices. (FLAC to MP3 for example; to play on a system that is not compatible with FLAC nor has enough storage to accommodate larger file sizes.)

3) You can instantly create the most awesome mix-tapes (aka playlists) you ever imagined as a teenager based on your library.

4) Your music library will be easy to organize, instantly sortable, searchable by multiple criteria, and easy to migrate to replacement storage systems.

Prerequisites for this project:

1) Enough storage on your home computer or home server to store your archive copy.

– One hour of CD music is going to consume roughly 300MB (rounded up) of storage in FLAC format.

– For a point of reference only: I’ve allocated 2TB for my sample archive – in which are stored a smidge over 1,000 albums, with around 13,000 songs, and consuming close to 300GB of disk storage. I plan to grow my library over time, so there’s another 1.7TB of free space left . . .

– Don’t forget backup storage too. You are about to put a lot of time (see point 3 below) and effort into a project that will benefit your digital lifestyle for . . . well, life! Make a backup of your entire archive and store it someplace safe.

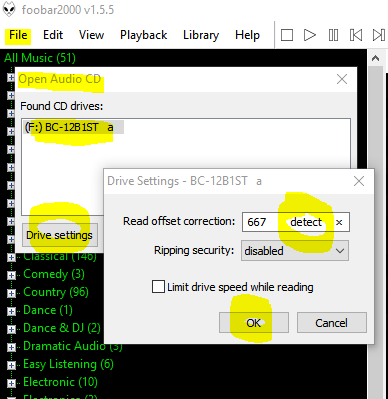

2) A computer with a reliable and fast CD player – either built in (using the SATA IO interface) or by fast USB (3.0 at least.) It needs to spin up to at least 42X normal speed for CD’s.

– A cheap but reliable example of a good fast internal CD drive might be the ASUS DRW-24B1ST, available online for roughly $20.

3) Time for the project. Not counting getting organized, nor the ten minutes we are going to spend together getting the system installed and ready, each one-hour CD will take from 4 to 15 minutes to rip, depending on the condition of the CD (Dirty? Scratched? Degraded substrate surface?) and the speed of your hardware.

– It took me about 90 hours or so to rip 1000 CD’s. Broke that down into hour long sessions in the evening. Each hour I was able to (on average) rip about 10 to 12 CD’s. Caffeine helps.

4) Software that can rip CD’s accurately and allow us to easily embed metadata for each music track. And that, my friends, is what we are about to talk about after this lengthy introduction!

That’s the intro – stay tuned for the next post in this thread on how to install and configure the software!

~ Group "Weekend" ~