|

ISSUE 16.36.0 • 2019-10-07

The AskWoody Plus Newsletter

In this issue WOODY’S WINDOWS WATCH: Shedding light on September’s out-of-band Windows patches PATCH WATCH: Finally! We have a true out-of-band IE update BEST OF THE LOUNGE: Things that should stay in the junk drawer LANGALIST: PC always boots into “Manufacturing Mode” DROLL TALES: LABS: Ian’s email account – Part 2 ON SECURITY: Are self-encrypting hard drives secure enough? WOODY’S WINDOWS WATCH Shedding light on September’s out-of-band Windows patches

By Woody Leonhard Microsoft delivered three different sets of patches in the past two weeks, all aimed at preventing a potentially devastating security hole known as CVE-2019-1367. The updates are still something of a mystery. Here’s what we know — and what you should do about them. What, exactly, is a CVE-2019-1367?

Malware researchers give security flaws numbers, assigned by a volunteer group known as the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures organization (site) within the MITRE Corporation. (CVE is, among others, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.) The vulnerabilities may get publicly acknowledged names at some point (e.g., “WannaCry” and “EternalBlue”), but the labels may change over time. The numbers (usually) don’t. CVE Details officially describes CVE-2019-1367 in this way: “A remote code-execution vulnerability exists in the way that the scripting engine handles objects in memory in Internet Explorer.” Microsoft defines it as a “Scripting Engine Memory Corruption Vulnerability.” It apparently isn’t a particularly pernicious beast; its CVSS score (more info) comes in at 7.6 out of 10. But as reported in my September 30 Computerworld article, when Microsoft first announced the IE flaw on September 23, it was listed as “Exploited” — meaning that Microsoft was aware of in-the-wild breaches. Not surprisingly, that set off the alarms. What does CVE-2019-1367 actually do?

Late Friday night, Susan Bradley provided a description of the flaw (AskWoody post) that isn’t accessible to “normal” Windows users. She quoted a post on the Windows Defender Security portal as stating: For attacks to be successful, targets will need to use Internet Explorer or another application that utilizes the Internet Explorer scripting engine to open a link containing the exploit. Initial reports of attacks indicate the use of Microsoft Word documents (.docx) with lure content that entice recipients to click on malicious links. If the links are launched by Internet Explorer — the default Web browser on machines running older platforms like Windows 7 — exploitation can occur. This analysis is based on limited, initial reports about actual attacks that exploit this vulnerability. Customers have encountered Microsoft Word documents (.docx) containing a link to webpages with exploit code for CVE-2019-1367. Although other distribution mechanisms are possible, we have observed attacks distributing the documents as attachments on spear-phishing emails. The documents themselves have been socially engineered with lure content — mostly around Middle Eastern and North African affairs — that entices recipients into clicking an embedded video element that is a link to external content. On many machines that run older platforms such as Windows 7, the link opens on Internet Explorer by default. Once the malicious link opens on a vulnerable instance of Internet Explorer, exploitation can occur, allowing attackers to run arbitrary code in the context of the current user. In known attacks, the exploit runs malicious code that does the following:

The executable, which now serves as an initial implant, then proceeds to download other payloads from another location. Mitigations Apply these mitigations to reduce the impact of this threat. Check the recommendations card for the deployment status of monitored mitigations.

How did Microsoft handle the announcement?

To put it bluntly: Extremely poorly! On September 23, Microsoft released a fix for all versions of Windows — from Win7 onward — that had to be manually downloaded and installed. Then, a day later, Microsoft released the usual round of “optional, non-security” (preview) cumulative updates for most versions of Win10 and the “Preview of Monthly Rollup” releases for Win7 and 8.1. The official descriptions didn’t say that they included the fix for CVE-2019-1367, but some highly educated snooping (thanks, @abbodi86!) revealed that the “fixed” version of IE was embedded in the “previews.” Three days later (September 26), Microsoft released the “optional, non-security” update for Win10 1903. (The “preview” release for this version always seems to be a few days behind the others.) Note that all of these fixes and fixes-of-fixes are optional — you have to go looking for them in order to install them. Even so, bug reports soon poured in. Confusion reigned. On October 3 — ten days after the initial “fix” release — Microsoft finally rolled out to all a third set of patches specifically for the CVE-2019-1367. This was a real out-of-band update: If you have automatic updating enabled, you should have received (or will soon receive) the patch. Lucky you. Still more complaints poured in. Most people who have installed the third set of “emergency” patches have had no ill effects. But a significant number of Windows users have complained — and are continuing to complain — about a wide variety of bugs. Most prominent among them is a printing problem. You install the patch, your printer stops working; you uninstall the patch, the printer starts working again. We also have some reports of the Start menu dying … and of JScript no longer working, and many others. We’re still getting reams of complaints on the AskWoody forum, here and here and here and here. What should you do?

Susan Bradley and I have been following the problems closely, as you might imagine. As of Friday night, we’ve come to a middle ground for our patching recommendations:

A big part of this quandary is the complete lack of consistency from Microsoft. First we get manual-install-only patches, suggesting the fix is not critical. Then we get fixes embedded in the monthly “optional” updates — again, not an indication of imminent danger. Then, a week and a half later, this oh-so-urgent “Exploited” vulnerability gets a full-court out-of-band update. No wonder we’re confused. Who’s minding the store? Patch Tuesday is tomorrow. You can bet the CVE-2019-1367 problem will feature in all October security and cumulative updates — which I will again recommend avoiding for a couple of weeks. Let’s just hope Microsoft cleans up the bugs. This bears repeating: Don’t use IE

With all the angst floating around over the latest patch problems, this much is clear:

Surprisingly, several AskWoody members have asked how to set a browser such as Firefox or Chrome as the default. It’s easy. Obviously, it starts with installing the browser of your choice. I use Google Chrome most of the time, but if snooping makes your skin crawl, try Firefox or one of many alternatives. Typically, setting your new browser as the default is part of the setup process. Just follow the instructions. What if the browser you want as the default is already installed? Here’s how to make the change in Windows: Windows 10: Click Start/Settings/Apps. (On older versions of Win10, you need to choose System.) In the left column of options, click Default Apps. Next, under the “Default apps” heading, find Web browser and click on whatever browsers Microsoft has chosen for you (usually Edge). In the “Choose an app” list, pick anything except Internet Explorer. You don’t need to click Save, just close Settings. Windows 8.1: Click Start/Settings, then pick Search and Apps. Click Default Programs, then select Set your default programs. Choose your preferred browser from the list and click Set this program as default. Windows 7: Click Start/Control Panel. Under Programs, click the Default Programs link. On the left, select the browser you want to use and, on the right, choose Set this program as default. There are many variations on the theme — most browsers have handy shortcuts in their settings that let you make them the default. But at its most rudimentary, the aforementioned paths should get you there.

Eponymous factotum Woody Leonhard writes lots of books about Windows and Office, creates the Woody on Windows columns for Computerworld, and raises copious red flags in sporadic AskWoody Plus Alerts. PATCH WATCH SPECIAL EDITION Finally! We have a true out-of-band IE update

After a series of confusing missteps, Microsoft has somewhat belatedly released an “urgent,” out-of-the-usual-cycle update in the expected way: All supported versions of Windows receive the patch via WSUS or Windows Update. This is how an “out-of-band” update is supposed to look and act. All Microsoft customers get protected quickly and easily. We don’t have to download anything from the Microsoft Update Catalog, install preview updates, or otherwise stand on our heads to be safe from a new exploit. In this case, the fix is for a newly revealed Internet Explorer vulnerability that Microsoft believes is already “in the wild.” Because the original update was buggy and not easily acquired, we strongly recommended that you not install it. And for non-business PCs, that’s still Woody’s recommendation. For now, he believes the cure might be worse than the disease. Indeed, some of the patch’s information pages now list up to four relatively minor “known issues” — but it’s likely there are more. Microsoft is now pushing out the latest iteration of this IE fix via WSUS and Windows Update — as it should have done from the start. Reportedly, these new releases clear up the print spooler and .NET Framework 3.5 problems discovered in the initial versions. After installing and testing the update on several types of PCs, I’ve not seen either of those problems. Some AskWoody members reported post-install problems with the Windows Start menu and other issues, but I didn’t see any of them on my systems. My take? I feel confident enough to urge PC managers to install the update — but be sure to check for printing and .NET issues. For home users, I don’t feel the risk (more info) is sufficient to warrant all this fuss. That said, if it got installed on your machines, leave it — and if not, don’t panic. (If you have automatic Windows updating enabled, the IE patch is probably already on your systems.) Here’s the list of the “out-of-band” Internet Explorer patches, released October 3: Windows 10

Windows 8.1/Server 2012 R2

(Install only one of these updates.) Windows 7/Server 2008 R2 SP1

(Install only one of these updates.) Windows Server 2008 SP2 and 2012

Stay safe out there.

In real life, Susan Bradley is a Microsoft Security MVP and IT wrangler at a California accounting firm, where she manages a fleet of servers, virtual machines, workstations, iPhones, and other digital devices. She also does forensic investigations of computer systems for the firm. Best of the Lounge Things that should stay in the junk drawer

“This won’t end well. Microsoft’s AI boffins unleash a bot that can generate fake comments for news articles” That’s the title of an article in The Register. If that spikes your curiosity, you’ll find a link to the story in a “Da Boss” Kirsty post. Outrageous? Sure thing. Expected? Nothing Microsoft does these days should surprise us. Certainly, this is one concept that should be relegated to the junk drawer. Cyber Security Susan Bradley leads us once again on a 31-day tour, just as she did last year with her series of posts: 31 days of paranoia. But this time around, it’s a 31-day tour of cyber security. Surprised by the subject matter? We’re not! Microsoft Office “Da Boss” PKCano posted a list of all October non-security updates for MS Office. They might not be critical, but the patches squash some annoying bugs and often add new features, making your Office experience more enjoyable. Microsoft Office AskWoody Plus member donihue is perplexed by PowerPoint crashes — when any keyboard key is pressed. Fellow Loungers offer suggestions to correct the problem. Join the hunt for a cure. Microsoft Office Lounger WSjsachs177 has a problem: graphics in documents won’t go away. They can be moved and resized but not deleted. Turns out, the solution was simple — surprisingly so! Windows 10 Pro Lounger dsliesse has a two-year-old Dell Inspiron laptop, fully updated with Windows 10 Pro 1903. But the machine is slow to boot. Task manager shows Bitdefender is partially to blame. With startup tasks set at a minimum, what can slow boot time down so much? Memory or hidden programs? Add your 10 cents to the discussion. Lounge matters Plus member geekdom wonders if there’s a filter to automatically block words that are not in accord with Lounge rules. If you’re not already a Lounge member, use the quick registration form to sign up for free. LANGALIST PC always boots into “Manufacturing Mode”

By Fred Langa A simple hard-drive upgrade triggered an unusual error. Worse, the problem defies common fixes and can’t be corrected from within desktop Windows. Plus: The clock on Windows 7’s formal end of life is now down to fewer than 100 days! A pernicious Manufacturing Mode glitch at every restart

Subscriber Mike Nettleton encountered a problem that I had truly never seen before.

Wow! Manufacturing Mode isn’t supposed to pop up in routine use — and certainly not after anything as commonplace as swapping out a drive. This specialized mode is normally used only by the original-equipment manufacturer’s (OEM’s) engineers when developing brand- and model-specific UEFI (info) settings for a line of PCs. These settings are then flashed (semi-permanently written) into the firmware of each newly manufactured mainboard during initial power-on at the factory. Typically, end users/consumers encounter Manufacturing Mode only after a complete mainboard replacement — or at the first power-on of a new, built-from-components, do-it-yourself PC. Those are not common events. A hardware change as simple and routine as a drive upgrade should never trigger Manufacturing Mode. Worse, in your case, Manufacturing Mode won’t let you fully into your system, and it comes back at every boot, even when you exit properly. To me, this suggests there are bad data in the new drive’s UEFI area or in a related, OEM-specific location. At boot, the missing or scrambled data make the PC think it has never been set up, so it enters its “ready-for-initial-programming” mode. But the PC is in fact set up, so you can exit Manufacturing Mode, the PC then will start, and it’ll seem to run fine — at least until the next boot, when the erroneous data cause another Manufacturing Mode stumble. Where did that bad information come from? You said your old drive was failing, so it’s possible that a serious drive error scrambled at least some data on the old drive — and this uncorrected error was then copied to the new drive. Or perhaps the cloning software messed up and scrambled or missed some data, especially if the data on the old drive were in a nonstandard or unexpected location. This can happen due to an OEM-specific setup or from more general events such as changing formats — say, from an old-school Master Boot Record (MBR; info) drive setup to the current GUID Partition Table (GUID/GPT; info). Windows offers scant help with Manufacturing Mode. Although you can enable it with Windows’ BCDedit.exe app, there’s no option for disabling Manufacturing Mode. (For more information, see the MS documents Enable or Disable Manufacturing Mode and Use the flashing tools provided by Microsoft.) With no easy software fix available, I think your best option is a simple do-over with a different cloning tool; it’s possible that the app you used was at least part of the problem. You want to create an entirely new image because the current cloned version contains at least one obvious flaw — and there’s no good way to know that there aren’t more. (In other words, I wouldn’t trust the current cloned image at all!) If a re-do with different cloning software also fails to produce a properly booting SSD, you can assume it’s probably not the cloning process that’s gone astray — there are probably bad data on the old drive. Which means further cloning attempts are likely futile, as they’d just pollute the new drive with the same erroneous information. If a second cloning attempt fails, I suggest you bite the bullet and get the new drive working on its own, with no data or anything else that might possibly interfere with the raw setup. Ideally, you’d perform the initial SSD partitioning and formatting with an OEM setup or rescue drive/disc. Using an OEM setup helps to ensure that the new drive will be configured correctly for your PC — including any/all OEM-specific and hidden partitions or disk locations. If you don’t have an OEM setup/rescue drive handy, visit your PC’s OEM support site. For example, see HP’s “Obtaining PC Recovery USB Drives or Discs” page. Once the initial setup is finished (partitioned and formatted), install a fresh, from-scratch copy of Windows (e.g., use Microsoft’s Download Windows 10 page) and then revisit your machine’s OEM site to obtain the best-available drivers. When the PC boots to Windows normally and without glitches, install your apps and use backups to restore all personal files. Yes, it’s a pain. But at the end of this process you’ll have a lean, clean — and fast! — SSD setup, free from whatever lingering traces remain from your old HDD’s problems. Windows 7 enters its final 100 days

Hey, Win7 users! As of this newsletter’s publication date (October 7), there are just 99 days until official support for the OS ends. Yes, Win7 will still run after January 14, 2020, but you won’t get critical security updates. If you’re still running Win7, now is a great time to make your move to a current operating system, whether it’s Windows 10, Windows 8.1 (EoL January 10, 2023), or even some distribution of Linux. By upgrading now, you’ll avoid the coming crush, as literally millions of Win7 users try to upgrade to Win10 at the last minute — as we know they will. It’ll also leave plenty of time for adjustments or recovery, should things not go 100 percent right the first time. Take the pressure off! Start the process today of getting your machine up to current standards.

Fred Langa has been writing about tech — and, specifically, about personal computing — for as long as there have been PCs. And he is one of the founding members of the original Windows Secrets newsletter. Check out Langa.com for all Fred’s current projects. DROLL TALES LABS: Ian’s email account – Part 2

By Aaron Uglum

On Security Are self-encrypting hard drives secure enough?

Microsoft has made a significant change in how its BitLocker encryption tool handles self-encrypting hard drives. Apparently, Microsoft doesn’t trust hardware-based drive security — should you? Surprisingly, the BitLocker change didn’t come in a feature release; it showed up in the end-of-September preview update for some versions of Windows 10. The following notification was buried in the long bullet-list of changes for KB 4516045 (Version 1803), KB 4516071 (Version 1709), KB 4516059 (Version 1703), and KB 4516061 (Version 1607): “Changes the default setting for BitLocker when encrypting a self-encrypting hard drive. Now, the default is to use software encryption for newly encrypted drives. For existing drives, the type of encryption will not change.” In other words: Before these updates, a new BitLocker setup would, by default, use hardware-based encryption on self-encrypting drives. After installing the updates, BitLocker will rely on software-based encryption — foregoing hardware-based encryption on new encryption setups. (If a self-encrypting system is already in use, BitLocker will continue to use it, by default.) So why did Microsoft make this shift? As reported in a ZDNet article in the fall of 2018, researchers at Radboud University, the Netherlands, discovered multiple vulnerabilities in some self-encrypting solid-state drives (SSDs) that could allow attackers to bypass user-set passwords. In some cases, a malicious hacker could simply apply an easily acquired master password set by the drive vendor. Before this revelation, self-encrypting hard drives sounded like an excellent idea. There’s no degradation in performance, and your data are automatically protected — or so we thought. In fact, prior to the September preview update, adding BitLocker might have left you less secure than you imagined. As a Tom’s Hardware article pointed out: “Those people [using BitLocker encryption] were actually worse off than anticipated, because Microsoft set up BitLocker to leave these self-encrypting drives to their own devices. This was supposed to help with performance — the drives could use their own hardware to encrypt their contents, rather than using the CPU — without compromising the drive’s security. Now it seems the company will no longer trust SSD manufacturers to keep their customers safe by themselves.” When the bad news broke, Microsoft released advisory ADV180028, which detailed how to change BitLocker’s default setting manually, using Group Policy. Some background on drive encryption

Full-drive encryption does two things. First, it protects data at rest. For example: Say you’re halfway through a flight, and you suddenly realize you left your notebook at the terminal. There’s no need to panic because you know the files on your hard drive are completely inaccessible, even if the drive is removed and attached to another computer system. (An unencrypted drive could allow someone to open and view any of its files.) Second, self-encrypting hard drives allow for “crypto-shredding.” Normally, when I decommission a drive, I literally destroy it — like, take a hammer to it and reduce it to pieces that no one is putting back together again. (And it lets me vent some steam in the process.) But indulging in a bit of pleasurable destruction obviously isn’t practicable with small mobile devices or with drives in data centers or any other location I can’t physically get to. The alternative — drive wiping — takes time and some effort. But on self-encrypting drives, you can just apply the crypto-erase technique. Instead of wiping the data, you simply delete or overwrite the drive’s encryption keys. You’ve made the data completely and forever inaccessible — in mere seconds, as shown in a YouTube video. Or so we once assumed …. We now know that at least some self-encrypting hard drives can be cracked — especially those in the consumer space that you and I buy. And it’s the reason Microsoft will no longer allow BitLocker to rely on hardware-based encryption by default — unless you override that setting. That change makes sense, but I’m wondering about Windows 10 1903 and 1809, whose September preview update apparently does not include the BitLocker change. It’s entirely possible that these two versions already include the change, but I’ve not found any confirmations on any official Microsoft site. But going forward, I’ll be testing to make sure that the setting is what I expect it to be. Checking and changing BitLocker’s encryption method

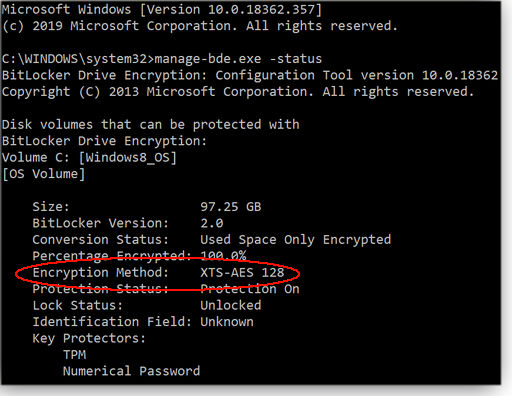

The most secure implementation of BitLocker uses Trusted Platform Module (TPM) — a tamper-resistant security chip on modern system boards — to hold encryption keys and check the integrity of the boot sequence. (BitLocker requires TPM 1.2 or higher, enabled in BIOS.) On boot, the chip automatically provides the encryption-key password. If you remove the hard drive and connect it to another system, there’s no longer a connection to the TPM and thus no access to the drive’s data. (TPM chips are different from the hardware that manages self-encrypting hard drives.) BitLocker will also work without a TPM chip — but it will demand that you enter a password whenever the system boots. So now that we know we shouldn’t completely trust hardware-based encryption, here’s how to check whether your BitLocker setup is using software or hardware to encrypt a drive. Enter manage-bde.exe -status into an admin-level command prompt. (Enter cmd into Windows search and select the “Run as administrator” option.) Look for the Encryption Method entries for each drive (see Figure 1). If you don’t see “Hardware Encryption” listed, BitLocker is using software encryption — and it’s not subject to the vulnerabilities associated with self-encrypting drives.

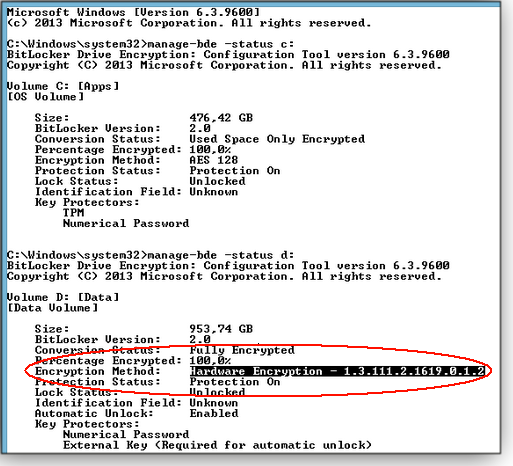

And if it does say hardware encryption? (See Figure 2.) You may have to undertake the tedious process of unencrypting the data, changing BitLocker’s method of encryption from hardware-based to software-based, and then re-encrypt your data.

Bottom line: Microsoft is doing the right thing by not trusting PC and hard-drive vendors. If you’re using BitLocker for data security, take the time to review the app’s setup — and decide whether you need to update it. In my case, I’ll use BitLocker with software-based encryption and ensure all of my systems don’t have hardware-based encryption enabled.

In real life, Susan Bradley is a Microsoft Security MVP and IT wrangler at a California accounting firm, where she manages a fleet of servers, virtual machines, workstations, iPhones, and other digital devices. She also does forensic investigations of computer systems for the firm. Publisher: AskWoody LLC (woody@askwoody.com); editor: Tracey Capen (editor@askwoody.com). Trademarks: Microsoft and Windows are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. AskWoody, Windows Secrets Newsletter, WindowsSecrets.com, WinFind, Windows Gizmos, Security Baseline, Perimeter Scan, Wacky Web Week, the Windows Secrets Logo Design (W, S or road, and Star), and the slogan Everything Microsoft Forgot to Mention all are trademarks and service marks of AskWoody LLC. All other marks are the trademarks or service marks of their respective owners. Your email subscription:

Copyright © 2019 AskWoody LLC, All rights reserved. |

By Susan Bradley

By Susan Bradley